Am I My Bitmoji Avatar?

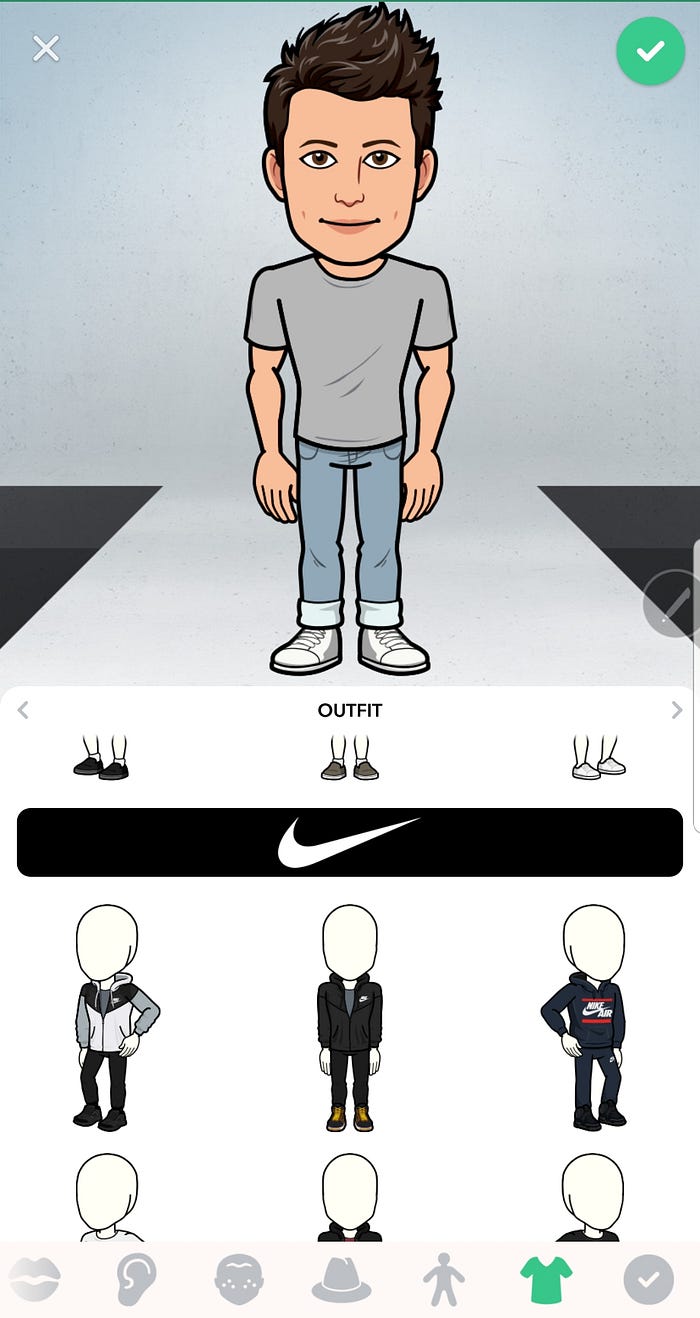

I spent the last 15 minutes designing my Bitmoji avatar for Snapchat.

Bitmoji is essentially an application that allows you to design an avatar based on your appearance. It begins by asking you to take a selfie, on which it then basis an initial proposal for the selection of your cartoon image, which you can then use within Snapchat posts, should you wish to personalise your content with what it calls 'stickers'.

Once you have given Bitmoji some idea about how you look, you can then select a number of characteristics in the style of your visible identity. This includes hairstyle, eye colour, eye shape, ear size, face size and shape, and eventually body shape and clothing style.

The first thing that struck me in this process is how limited we are in choosing an avatar that corresponds with age. As hard as I have tried to create my avatar in my likeness, I think it looks like a 20 year old version of myself. I am not sure whether I have created an image of how I would like to look, or perhaps how I imagine myself to look. Perhaps, I have imposed upon this process the desire to look younger than I am.

However, I suspect that this younger version of myself is more a product of the Bitmoji system than of my bias. After all, Snapchat is mostly used by very young people.

There are some interesting integrations within the platform, such as the ability to choose clothing that derives from an actual retail outlet or clothing designer. Many of these companies are mostly located in what I would describe as an American consumer market, and includes such brands as Nike Adidas Hollister and even NBA style clothing.

Such geographic bias within the clothing style of these avatars, limits Bitmojis capacity to be inclusive and while it might seem facile to complain about the lack of inclusivity within Avatar design, I also think that the bitmoji is indicative of a wider culture of image manipulation which we can trace over many more years.

Consider the way in which Photoshop remains a verb that describes the process of modifying the otherwise true record of our lives. We find the use of this term within moments of popular culture, which refer to how we might 'photoshop' an image to create a preferred version of our reality.

It is curious that we tend not to think about such activity as fake news in the way that we do today, but perhaps there is a deeper connection that we ought to tease out between that era when image manipulation because an accessible technical possibility and our more recent preoccupation with fake news.

While image creation has always been and interpretation of reality, the demise of the camera as a device which aspires to capture the world as it is is brought about precisely by the rise of the computer generated image.

With its clothing brand integrations, we witness the economic infrastructure that sits behind the platform and, as a consequence, find ourselves within a post-modern reality where our consumption of a product or brand becomes entirely divorced from its functional presents within our physical lives.

While clothing has not been simply functional for many years - if ever - its having become a digital cartoon product is perhaps the culmination of how far we have come within consumer culture from attending to crucial human needs. While one does not need to pay a price within bitmoji for these clothing products, it is not difficult to imagine this becoming an optional extra, especially when the the clothing is presented as being of the latest season outfits.

These observations about bitmoji must be couched in a recognition that a pre-digital sociological analysis may not be particularly meaningful in a post-digital environment. In other words those concerns we have about categories of distinction may simply not apply within a present times. After all the manner in which digital citizens manipulate photographs of themselves to a point of complete absurdity, shows us that digital allows us to step outside of a representative framework of image creation. The exaggerated enlargement of our eyes or cheekbones for instance, are indicative of this possibility that representation has ceased to be an aspiration of photography.

In any case, it is crucial that we remain vigilant to the manner in which our options within a digital world may restrict our freedom to be inclusive, or to raise questions of inclusivity, else we risk losing sight of these concerns as critical aspects of our aspirations for society.